Lightform 1.0: exploring ubiquitous projection displays, connected art objects, and projector industrial design

Lightform was founded late 2015 with the goal of creating a turnkey platform for projection mapping. Projection mapping has historically been limited to high-budget events due to its cost and complexity. The technique, however, has many applications beyond large scale entertainment including art, signage, and ubiquitous computing. Lightform sought to distill the technique into an affordable, all-in-one system that was simple and attractive enough to install in residential, hospitality, and retail environments.

This post documents early proofs-of-concepts created in early 2016. In August 2016, Lightform was acquired by Lumenous3D, which adopted the Lightform brand and currently exists at lightform.com

Much of this post is covered in my FITC 2018 Talk: “Designing With Light: The Upcoming Wave of Ubiquitous Projection” embedded below.

Early Inspiration: Digital Art Displays

Around this time, there was a wave of startups including Electric Objects, Framed, and Depict making turnkey digital art displays. These were essentially screens with embedded computers and mobile apps where users could browse marketplaces of digital art files. Most screens were only available in portrait orientation, and featured customizable wooden frames to visually distance themselves from ordinary computer monitors and televisions. The attention to industrial design and incorporation of natural materials emphasized their purpose: these were not purely practical devices, but rather beautiful objects designed to celebrate their content and complement their physical surroundings.

Electric Objects EO1 (2016)

Samsung Serif TV

Samsung Frame TV

Of the startups, I found Framed the most interesting because it had enough processing power to run OpenFrameworks apps. This allowed artworks to render in real time as opposed to static image and video playback.

Framed 2.0

Framed also incorporated an RGB camera into the bezel that allowed basic interactivity. Artworks could react to motions and gestures, or create “magic mirror” style effects. Clay Bavor, now head of Google VR, proposed other interesting uses for a camera, including ambient light adjustment and “shy mode,” where art would only change if no one was looking at it. This simple form of spatial awareness hinted at a larger question: if a display knew who was looking at it and when, how could it change to accommodate the viewer?

Framed 2.0 artworks

Art as Computing Interface

Digital artwork can be personalized by its owner. An artist may create an initial set of rules with code, but the piece can remain dynamic via sensor input and real time data streams. If the data is of personal relevance to the owner — the local weather, for example — the artwork now provides functionality beyond pure aesthetics. Sidestepping the semantics of art vs. design, if an artwork can give and receive digital information, it has effectively become a computing interface.

Light art, IoT device, or both?

I was fascinated by this intersection of art, lighting, and computing because I believed it to be the true promise of augmented reality and the "Internet of Things." These art displays weren’t simply taking something analog (picture frames) and making them digital. They were taking something that was already digital, something we already consumed via general-purpose computing, and giving it a dedicated, physical manifestation. They were breaking digital art out of our computers.

When viewing these displays, there was no way to get distracted by Instagram or Facebook. There were no email or text notifications. You couldn’t switch apps to make a phone call or FaceTime. They basically did one thing: display digital art.

As computing becomes more ubiquitous, could breaking more tasks into their own tangible interfaces gradually reduce our dependence on mobile and desktop screens? Could simpler, computers with fewer distractions ultimately allow us to be more human?

The Light Phone is an anti-technology "dumb phone" intended as a temporary stand-in for your smartphone. Is another device the ironic solution to technology overload?

Avoiding Connected Home Pitfalls

Unfortunately, outfitting everything down to our toothbrushes with Wi-Fi hasn’t exactly achieved the human-centered technological utopia of our dreams. In many cases ubiquitous computing is helping us save time, conserve energy, and live better; but during this awkward growing phase we’ve also inundated ourselves with more notifications, software updates, and security vulnerabilities — just like our desktop and mobile devices. Has the Internet of Things lived up to its promise or just created more sources of interruption?

Jake Levine, founder of Electric Objects, spoke frequently about making computers that “don’t demand your attention,” a reference to the concept of “calm technology” originally coined by Xerox PARC Researchers Mark Weiser and John Seely Brown in 1995. The concept was further developed by Amber Case in her 2016 book by the same name.

Calm technology describes a form of computing where “the interaction between the technology and its user is designed to occur in the user's periphery rather than constantly at the center of attention.” A simple example of calm technology is an indicator light, such as the lavatory signs on an airplane or the status LED on a Wi-Fi router. These are simple visual extensions of larger, more complex systems, and they exist in the periphery, never interrupting us from our current activity. We only consult them when necessary and can quickly obtain the basic information we need: available or not.

The most successful connected home devices employ calm technology principles. When working correctly, they run smoothly in the periphery and are rarely noticed. For example, smart lights and thermostats that employ geo-fencing to automatically turn off when no one is home. Or the quintessential recent example: voice assistants that are there when you need them and invisible when you don’t.

Google Home voice assistant

Of course, when the tech fails we really notice. Debugging connectivity issues on our smart pet feeder is not how we enjoy spending our time, and in fact, takes us longer than just feeding our pet the old-fashioned, analog way.

In the age of internet-connected everything, it seemed that art and design objects were the smart home’s next frontier. But could we avoid the same pitfalls that plague other IoT devices? Could these objects be simultaneously decorative and informative without becoming distracting? Does adding interactivity to something purely decorative impede it’s value for ambiance? At what point does it became just another computer? Was any of this even worth doing?

Philips Hue IFTTT recipes

Digital Decor, Calm Technology

I believed the answer was yes, digital art and design objects could be simultaneously decorative, informative, and “calm.” The art world is full of beautiful data visualization pieces, but they exist on a grand scale beyond the price range of most consumers. Moving these works from site-specific installations to homes was simply a matter of miniaturization, Moore’s law, and a UX that enables personalization.

Virtual Depictions by Refik Anadol, commissioned for the 350 Mission Building in San Francisco. A series of data sculptures visualize local weather patterns and social media activity.

For example, a landscape portrait could convey local weather forecasts by superimposing rainclouds or changing lighting. A poster of a local map could indicate how far away your bus, rideshare, or delivery is. An LED light sculpture could indicate a friend’s flight status or electric vehicle charge by advancing along a simple color gradient. A planted pot could let you know when it needs watering with a minimal indicator light. A wall clock could indicate commute time or upcoming calendar appointments using simple patterns.

Because these objects are embedded into our environment, they free us from constantly referencing desktop and mobile devices. We can passively absorb simple yet important information through unobtrusive audio/visual cues, allowing us to read a book, prepare a meal, or hold a conversation without interruption. We can choose to switch contexts by physically moving through a space or shifting our gaze, not just switching between apps.

I set out to validate this theory through a series of experiments.

Projection's Advantages

At the end of the day, the digital art displays that captured my interest were still just fancy screens. The interfaces were constrained to rectangular aspect ratios, planar surfaces, and a matte or glossy finish. When turned off, they leave space-consuming black voids tethered by power cables.

Images looked nice, particularly on matte displays, but were never quite like the marketing materials which depicted them as equivalent to analog. They existed in a sort of “uncanny valley” for art. Something artificial was trying too hard to appear natural instead of just owning it. Also absent from the marketing images were the power cables, which further added to the visual distraction.

BERG - Lamps

Projected light, on the other hand, is additive. It has no volume, so it overlays objects instead of displacing them. Negative space is simply the absence of light. It’s the underlying material, not a hunk of glass and metal.

Projection lets designers break interfaces out of the screen and into the real world. It facilitates tangible computing, a concept pioneered by Hiroshi Ishii at MIT Media Lab’s Tangible Media Group that involves adding digital interfaces to physical objects. Many groups have since explored interactive projection mapping as “smart light” or “interactive light,” including design research firms Berg and Argodesign, and Bret Victor and Alan Kay’s ongoing research project, Dynamicland.

Dynamicland

Argodesign - Interactive Light

Projection is also an inherently calm display technology because it can disappear. When projection is off it fades into the background, leaving only the native object or architecture. Projected interfaces need only occupy a space when contextually appropriate.

Screen future?

Projection future?

Therefore, in the context of art and decor, projection can augment analog objects we already own. It’s a concept BERG called “dumb things, smart light,” and I was interested to see how it could be applied to objects I interacted with on a regular basis.

Experiment 1: Projector Industrial Design

Projection interfaces are more minimal than screens, but the hardware necessary to create them is not. Recent advances in LED and laser light engines have rapidly shrunk projectors, but there was still no product that combined projection, sensing, and computing into a single device.

Goals: LF-T track mounted projector concept

Reality: State of the art pro-cams (2016)

Manufacturers like Panasonic and Beam Labs have attempted to address the installation and industrial design problem by offering projectors that resemble light fixtures. However, an integrated device that includes a projector, camera, and computer still does not exist.

Beam, an LED projector "lightbulb"

Panasonic's Space Player, a track mounted laser projector

I began evaluating various small-form-factor computers, cameras, and LED projectors to see what was possible with current off-the-shelf hardware.

Experiment 2: Track Mount + CNC Releif

My initial project involved designing and fabricating a custom relief for my dining room. The design was modeled in Cinema4D, and had to consider certain constraints around projector placement and shadows. Because I was only using one projector, I had to ensure that all the faces of the relief were visible to the projector’s lens. In the future, this issue can be addressed by using multiple projectors, but there will likely always be under-hangs that are tough to reach via ceiling-mounted projectors.

Content was rendered in realtime using TouchDesigner on an Intel NUC, and was controlled via OSC using a custom app built in Unity.

Experiment synchronizing color gradients with LED smart bulbs

I found that the width of the LG PF1500 nicely matched the interior dimensions of a PAR38 track light fixture. Track lighting has become less prevalent in residential, but is commonly found throughout retail and offices. Single circuit “H” track is standardized across brands, and accessories are widely available locally and online. Once installed, track lighting offers flexibility when placing and moving fixtures, and does not require any additional wiring.

While I found the projector mount relatively clean, I did not love the overall aesthetics, which prompted a later re-design.

Experiment 2: Floor Lamp + Ceramic Vase

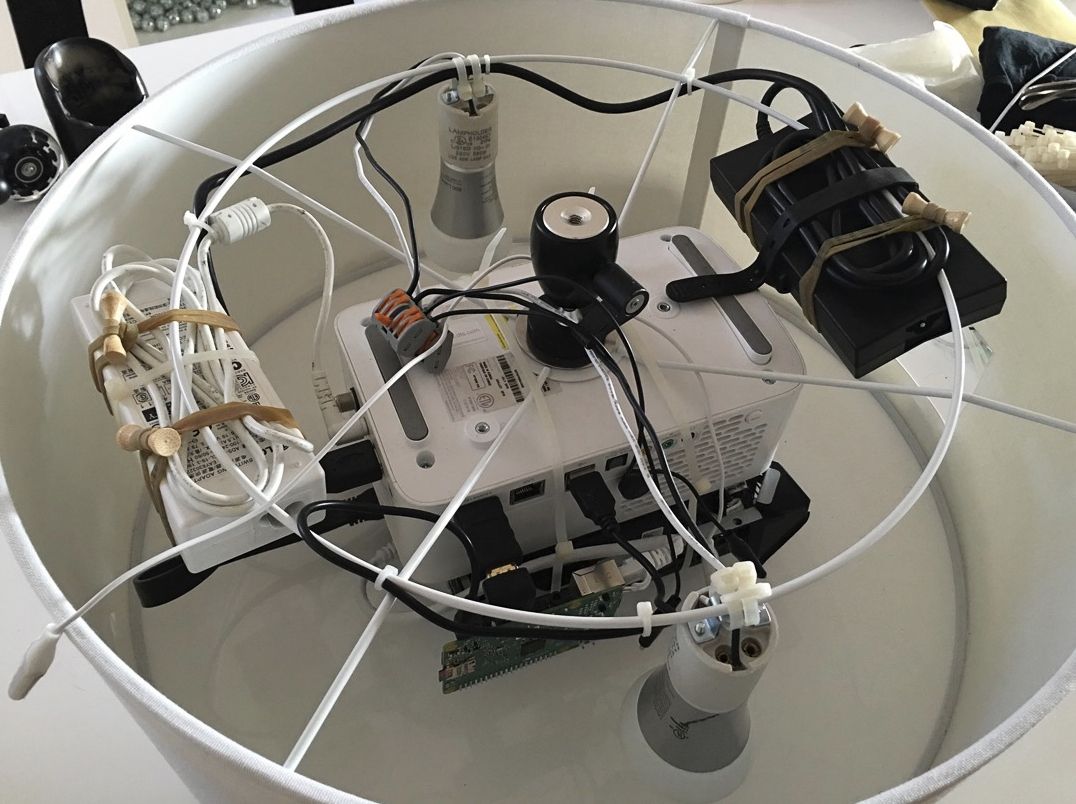

In order to explore a more portable design, I purchased a tripod floor lamp rom EQ3 modified the the base and shade to hide the PF1500. With this setup I demonstrated a plant watering notification concept. If simple objects like the ceramic vase were embedded with minimal electronics, such as BLE moisture sensor, they could communicate with an external projection system that can in-turn provide a subtle visual cue.

As computer vision and machine learning advances, the BLE sensor could be done away with entirely, as the pro-cam system could learn watering patterns and plant species through direct observation.

Experiment 3: Picture Frame + Marble Clock

Wall clocks are quintessential, functional design objects.

Taking advantage of the fact that most consumer projectors have 100% lens offset, I attempted wall mounting the LG PW800 and disguising it behind a picture frame.

Definitely bit of a "Lamps" homage, but particularly trying to explore where the Internet intersects art & decor. Inspired by digital art display startups such as the ultimate goal was to create a system that simplified the process of installation

LG MiniBeam, Intel NUC, Power Supplies